The Top Ten Heroes of Horror

Written by: Emmet O’Cuana

Being a ‘hero’ in a horror novel is a bit like trying to have a rational conversation on the internet, or wandering out into the middle of a demolition derby track and flagging down a passing vehicle. It is going to get messy fast. The fear of death is a constant in horror fiction, so either the protagonist themselves die, or they fail to defeat the monstrous threat. This is why there are no books by H.P. Lovecraft featured on the list below. His characters are doomed from the first sentence – heroism being effectively non-existent in his stories of cosmic nihilism.

Not all of the names below save the day, get the girl/boy, or ride off into the sunset as we have come to expect from our heroes – but they made a difference. There will be some surprises and certain old favourites too.

Victor Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s romantic scientist was a trailblazer in more ways than one. In bringing a corpse back to life he bent God over his knee and gave him a good spanking, ecumenically speaking (inspiring the original subtitle ‘The Modern Prometheus’). In addition Victor Frankenstein is the first of a new breed – the mad scientist. Shelley single-handedly created a new literary genre in science fiction and instituted a number of tropes that persist to this day.

The sense of horror in Frankenstein comes from Victor refusing to deal with the consequences of his classical hubris. The Monster is at times inscrutable, alien – but also deeply sympathetic. Unlike the mumbling, shuffling creation of Hollywood and James Whale, Shelley portrays It as a passionate Byronic figure. Without the club foot and STDs. In a sense Victor has not only managed to replace his God, but gone and created his own Lucifer as well. Frankenstein remains a compelling read, its hero slowly realizing that he himself has become a monster.

Arthur Gordon Pym

This entry is something of a cheat, as Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket was identified by H.P. Lovecraft as a key influence on At The Mountains of Madness. So consider Arthur an honorary member of the Lovecraft club.

Poe’s story draws upon the diary of an unfortunate seafaring traveller, making it something of a 19th century Blair Witch Project – although the epistolary horror novel was a popular device during the period. This allows Poe to have Pym describe in gripping detail the effects of starvation and desperation on himself and his dwindling crewmates as they travel towards the unknown regions of the South Pole. In a certain sense, Pym sees himself as an instrument of science, not only accounting for everything he witnesses, ensuring that he leaves behind evidence of his passing for another to discover. Yes this story does not have a happy ending. It also took advantage of the reading public’s lack of knowledge about this part of the world. The author could afford to introduce the weird wonders featured here. In that sense Pym is one of a dying breed, an explorer of the unknown.

Van Helsing

Bram Stoker introduces the final attempt to save the life of Lucy Westenra by having a gathering a devoted men – Lord Godalming, Quincey Morris, John Seward and Van Helsing – donate their blood to help her fight the vampire infection. The Dutch nosferatu hunter jokingly describes this as a marriage contract to Seward – the men are all now bound to Lucy. Stoker’s unusual notion seems to be that each of the men are now betrothed to Lucy in a sense, so that if she should die she will not die in sin. It is a bizarre idea, but points to the time of its writing. The Christian values of Victorian Britain focused the reader’s attention on the state of Lucy’s soul, with Dracula representing both a physical and spiritual threat to her.

Van Helsing himself jokes that he is now a bigamist, as his dead wife is waiting for him in Heaven as part of his binding contract with the Church. As a character he is the grandfather of every vampire slayer that follows after Dracula’s publication – but he is also pitched perfectly between the superstitious past and the unwitting future of teens with stakes in their handbags and sparkly vampires. Van Helsing is simultaneously a relic and a horror fiction pioneer.

The Governess

Henry James’s prose has a difficult reputation for being dense and over-descriptive. Portrait of a Lady has great moments that make the slog through endless exposition well worth it – but it is a slog nonetheless. Which is why The Turn of the Screw is such a relief to read. A tense and psychologically nuanced novella by James, it manages to be both an unforgettable ghost story and an excellent piece of writing.

The nameless twenty-something narrator of this story is troubled by the growing realization that the two children in her care are being visited, possibly even molested, by a pair of ghosts. Due to the first person narration readers have long debated whether the heroine is actually insane, imaging the events described. William Archibald and Truman Capote worked on the screenplay for the film The Innocents, which explored this idea quite well. Even the shocking ending of the story is ambiguous, the reader left just as bereft as the Governess herself.

Thomas Carnacki

A century before the world went mad for The X-Files, William Hope Hodgson had nailed the concept of the skeptical ghost catcher. In fact Carnacki manages to be something of a two-for-one offer, having traits of both FBI agents. He is a relentless investigator of supernatural con-men, but also happens to believe in ghosts and magic.

Though only featuring in six stories by Hodgson – himself in life a fascinating character – Carnacki is an icon of horror literature. His stories begin with a group of acquaintances joining him for a drink and a smoke as he prepares to tell them about his latest adventure. It’s a given that Carnacki himself will survive – the suspense comes from whether the people he meets will have an unpleasant end at the hands of a spirit, or a devious fraudster hoping to frighten them to death. Hodgson’s imaginative use of the public’s fascination with technology – Carnacki uses an ‘electric pentacle’ to capture ghosts – cleverly played to modern concerns while also elaborating on established supernatural themes. Your Felix Castors, Harry Dresdens and John Constantines can all be traced back to this diffident Edwardian gentleman.

Robert Neville

And here is one of Van Helsing’s descendants. Neville is the scientist besieged in his home each night by his friends and neighbours turned vampires. During the day he hunts them in their nests and stakes the sleeping fangsters. Richard Matheson’s novel perfectly captures the loneliness and paranoia of his protagonist, with no small amount of humour in amongst the horror. For example after meeting the first living woman he has seen in years, the two talk about their likes and dislikes, with Neville internally sneering at her love of Rachmaninoff. She’s the only other live person you’ve met and you’re being a snob! You fail at the Last Man on Earth sex fantasy Neville!

I Am Legend is a tense, claustrophobic story of one man’s refusal to give in to depression and madness. As a novella it remains as compelling as when it was first published. As a hero, Neville continues to endure.

Colonel Christina Eliopolis

Strictly speaking the ‘hero’ of World War Z is its interviewer Max Brooks, who travels the world meeting the survivors of the zombie apocalypse. This is one of the many reasons the upcoming film looks terrible, as by seemingly missing this key note of horror from the book it is transformed into an action film with hints of horror. The book instead questions what would you have to do to survive such an apocalyptic event? And how could you live with yourself?

Eliopolis’s story is one of the most powerful in the collection of personal accounts – one which would have been great to see on the big screen. Stranded in a zombie-filled swamp, with only a lone voice on her radio to guide her, Eliopolis shares a similarly indomitable personality as Robert Neville. Brooks then introduces a fascinating note of ambiguity that leads the reader to question her recollection of events. There’s plenty to enjoy in World War Z, but this particular story combines thrilling action and explores the psychological cost of survival.

Will Navidson

Will is one of three principal characters in the mind-bending novel House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. First there is Zampanò an elderly man who is already deceased at the beginning of the story, but whose voice remains in the margins (literally) of the book we are reading. Then there’s Johnny Truant, a petty criminal and junkie who becomes obsessed with Zampanò’s research. Will Navidson is the unknowing focus of both men’s obsessions. He is the ‘hero’ of the book, because it is his story that lies at the heart of House of Leaves.

Danielewski’s book is a modern-day take on Poe’s Pym, but with today’s multimedia fixations – the book was accompanied by an album released by the author’s sister named (wait for it….) Poe, with Haunted a companion piece to its fraternal novel. Navidson films the strange events that happen to his family and then his bizarre journey into the TARDIS-like interior of their home. The book’s own text formatting becomes strange and aggressive, brilliantly creating the impression in the mind of the reader of Navidson’s delirious mental state. House of Leaves is one of the great horror novels and Navidson – the thrill-seeking war-photographer turned loving family man – is its very human heart.

Oskar

John Lindqvist’s Let The Right One In is one of the best vampire novels ever written. Oskar, the vulnerable young boy who befriends the child-vampire Eli, is its dubious hero. Is he a lovestruck kid, helping this ‘girl’ due to his own loneliness? Or is he a Renfield in-the-making, helping to protect a monster?

Oskar is not only baffled and depressed by his parents’ divorce. He is growing up in Sweden during the 80’s with rumours of Soviet subs prowling off the coast. Before he even discovers the existence of vampires the world is already a terrifying and loveless place. Eli becomes his escape from a life that he has already grown to hate, with Lindqvist brilliantly realizing the boy’s frustrated anger.

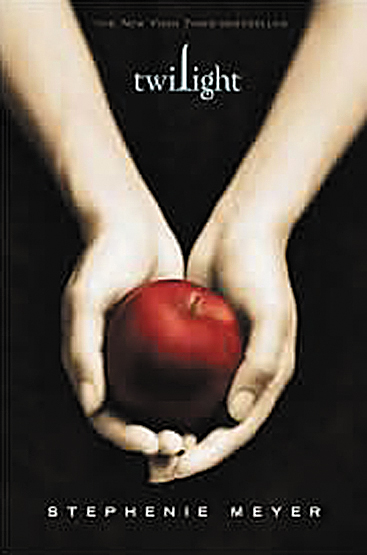

Bella Swan

What? Twilight!? Well yes…cards on the table, these are terribly written books, with plots that barely deserve to be called such – but! Stephenie Meyer unleashed horror publishing phenomenon. Horror itself was changed, with a multitude of books – call them Paranormal Romance or Dark Fantasy titles or whatever you like – aping the simple cover aesthetic of the Twilight series and captivating an entirely new demographic. Cash-registers round the world were set a-ringing to a pitch not heard since Stephen King’s 80’s heyday.

At the centre of all this fuss is the Mary Sue-like Bella, a character who is defined by her lack of qualities – easier for fans to therefore exchange their place with her then – as well as her klutzy nature. This physical ineptitude is revealed to be a sign she was meant to be made a graceful vampire. It’s such a striking inversion from Lucy Westenra’s gratefully thanking Van Helsing for his watchful actions at her deathbed, to Bella gleefully embracing vampirism, with the author making clear ‘this is a good thing’. Call it the great anti-feminist statement of our time, but her iconic status clearly indicates where wish-fulfillment today lies. Bella is a poster-child for readers who want to retreat from the modern world.

// //

Hot damn. this is one awesome, eclectic list. Job. Damn. Well. Done!

LikeLike

Cheers mate.

LikeLike

Fantastic catalog of gems here old and new. Some really intriguing ‘left-field’ choices. Great stuff.

Wholly agree with your assertion on the upcoming ‘World War Z’ movie, but then it’s hard to expect anything more than commercial pap after hearing Brad Pitt say he wanted to make a zombie movie he could take his kids to see. Ugh….

LikeLike

I feel World War Z had all the makings of an amazing faux documentary that happened to be about zombies. Talking heads interviews with traumatized survivors, footage of urban massacres recovered from wreckage, perhaps an anime recreation of the ‘Zatoichi’ pastiche…

LikeLike

Couldn’t agree more. Just hope Max Brooks doesn’t have to spend this Summer apologizing for what the Hollywood threshing machine has ‘probably’ done to his novel…

LikeLike

Great list, even more fodder for future reading! I would like to personally add a number 11, that is the dedicated monster hunters of Special X in the Michael Slade novels. I mean face it, they’ve removed some nasty bad guys over the years, at great personal literary cost!

LikeLike

Some really good selections here, but I definitely take issue with Bella Swan. As successful as the Twilight franchise was, it was absolutely never marketed nor written as a horror franchise.The description of what qualifies her as a “hero” doesn’t at all match up with anyone else on this list…. she saves no one, she changes nothing, she is, as is pointed out, “wish fulfillment”. Comparing her with Van Helsing, or Robert Neville, is just pandering. Unleashing a “publishing phenomenon” does not a hero make.

LikeLike

Exactly! She’s entirely out of keeping with the rest of the entries, which is why I raise her as for some reason she *is* considered ….admirable? Relatable? It confuses me.

So is the idea of what makes a hero shifting? The fact that the qualities I find so insipid are revealed to actually be deliberate because her humanity is somehow a …failing in and of itself. Well that’s baffling to me.

It has changed horror. There is no one fixed definition of what makes a scary book, but you will find writers of the genre either aping or confronting the conventions of Twilight – because it sells.

LikeLike

So, it sounds like you as the author are not even sure why you included her, which is not at all helping your case. There were literally hundreds of better characters to fill that spot.

No, there is not one fixed definition of what makes a scary book, but I have never heard anyone anywhere describe Twilight as “horror”, including the author. There are literally no horror elements in it. Even the use of monsters isn’t horror because they aren’t a threat to any human population. It’s straight-up romance with a paranormal twist, and if you’re going to include that sub-genre as part of “heroes of horror”, why didn’t we get to Laurell K Hamelton’s FAR superior characters? Or hell even Anne Rice? It sounds like the only reason you picked this is because of commercial success. That’s a pretty lame way to define a hero.

I don’t think Twilight has changed horror at all. I think it’s changed romance, because it’s a romance novel.

LikeLike

Basically I see that you’re trying to ask a question here, “does the idea of what makes a hero shift?”, but your list here is supposed to be ANSWERING that question, not asking it, and it doesn’t sound like you can actually defend the choice to include her. If you could make a case beyond commercial success, I’d be willing to consider it, but it doesn’t sound like you’ve got much else to go on.

LikeLike

The claws are out! I love controversy 🙂

Sent from my Windows Phone ________________________________

LikeLike

I actually think you could mount an argument that Twilight uses elements of gothic fiction/horror – it’s character roles, the storyline, horror monsters, romance. Although it is very much on the ‘lite’ side, but I don’t think anyone is saying otherwise.

This is where I think Twilight has changed horror, in that its use of the traditional horror monsters has opened up the genre to a whole new audience, whose expectations of them have now changed. Consider it, maybe, a gateway drug? Bella Swan is perfect for those with a peripheral interest in the various supernatural-type creatures but who can only deal with a little bit of the icky stuff, or the idea thereof. So who knows what the success of the books and the films will be, we can’t actually speak to that just yet.

I for one find the whole concept of a child eating its way through my lower bowel pretty damn terrifying.

Also, I think its inclusion is a little tongue in cheek.

LikeLike

Even if a cessation is made in granting Twilight some kind of lite-horror status– and I’m not saying a cessation should be made, especially based on a single graphic scene in the book– I’m still not hearing any reason why Bella is any kind of hero. Even by her own universe’s standards, she was never in danger and so never needed to save herself; she never needed to save anyone else; her interests were entirely of a romantic and self-involved nature and nothing more. To put her in a club with Neville or the soldier from WWZ is completely diluting the definition of “hero”. Besides, authors were doing this “paranormal romance” twist WAY before Twilight; this was just the first series that was “kid-friendly” enough to get a wide audience. Again I point to authors like Laurell K Hamelton who have been mixing monsters and romance for a very long time. Twilight stepped through a doorway that has been open for decades, it didn’t create it.

In the end, I understand what this list-maker was trying to accomplish, but he did a very poor job of quantifying what he was basing his decisions on (IE: What makes a hero), which makes at least Swan seem completely arbitrary, like it was meant to be some “surprise twist ending” with no point other than to shock. Not once on this list was “commercial success” or popularity a qualifying factor in a character’s inclusion, except Bella. If it was “tongue in cheek”, it was not delivered well, and it shouldn’t take a follow-up comment to make that clear.

LikeLike

We have a list of characters sampled from other two hundred years, during which the notion of horror and heroism has clearly shifted multiple times.

By the very fact that Bella is a wish-fulfillment character, what does that tell us about the value of heroism today, of what readers are looking for in their fiction?

The complaint listed seems more inspired by including Twilight at all in a discussion of horror. Unfortunately our individual tastes do not define what is or is not a part of this genre. What is successfully sold to a majority of readers does. Call it whatever you like, but it has changed horror, as said before in either an imitative or reactive way.

LikeLike

If that’s your take-away, you’re not doing a very good job reading my replies. My main problem here is you’ve failed to quantify what makes her a hero beyond the commercial success of her series, which is especially strange when commercial success has not affected a single other entry. You keep asking me “what does her commercial success and her as a wish-fulfillment character tell us about the value of heroism today?” and I’m saying: “Nothing– because I have clear definitions for what constitutes a hero in a story and Bella has none of them, therefore she has no bearing whatsoever on the conversation of heroism in today’s literature” I’m asking you to explain and justify why YOU believe she has bearing on the conversation of heroism.

If you really want to bring Twilight into a heroism conversation, why isn’t the character listed Edward? Or Jacob? Or one of Edward’s brothers? Why did you pick Bella? I can’t answer these questions, because you’re all over the map and have failed to identify by what standards you are choosing heroes for this list. I don’t care if Twilight is on a list of horror novels; it’s not how I look at the series, but you’re right, that’s individual taste. What I DO care about is that you’re telling me this is a “Top Ten Heroes of Horror” list, a far different distinction. Now you’re ranking. And when things are ranked, it follows that characteristics must be distinguished by which to judge the contenders.

Next time you choose to rank things, I highly recommend you first set aside quantifiers by which you will measure your entries. If “commercial success” is one of your quantifiers, then House of Leaves should not be on this list, nor Thomas Carnacki (nor, by all rights, Poe, since his success was posthumous). Again, you’re all over the map, and it completely discredits every entry on this list when you’re not following any sort of standards on making these judgments.

Your opinions about Bella vis-a-vis what the modern reader thinks about heroes is a perfectly legitimate conversation to have. Write a whole essay about it and tell us about this question you have. But a top-ten-heroes list is not the place to ask that question. Lists are meant to answer questions.

LikeLike

Well no, I don’t feel a list should tell people what to think. It’s a list. It’s intended to introduce discussion. I have been directly asking you questions as part of this thread to see what you think, not to insist on my own view.

Popularity has everything to do with heroism as depicted in fiction, because it represents what people want to see. We are not talking about qualities that you or I might admire – we are talking about what a majority of people identify with/aspire to in their recreational reading. Twilight fandom is a clear demonstration of a large upsurge of interest. Every other character on this list is also present for the same reason. If Frankenstein had not been a bestseller we would not know about it today and so on. Posthumous or not that we are reading these books in 2013 shows they have not ‘failed’ to attract attention, so your point is invalid.

I was actually going to propose we write rival articles on Bella, as that might be more productive than this discussion.

LikeLike

Thanks but no thanks on the articles, I don’t care quite that much about Bella or what people think of her to invest the time and research an article like that would require.

However, I will agree to disagree with you. I still contend that your work here is confused; you say heroism “represents what people want to see” and/or “what a majority of people identify with/aspire to in their recreational reading.” but yet have also left out Lovecraft’s work thanks to “heroism being effectively non-existent in his stories of cosmic nihilism.” Yet Lovecraft still attracts plenty of recreational readers– readers who are inspired by his characters’ sense of action despite the nihilism in their world, readers inspired by his characters’ intelligence and investigation abilities, by their bravery in the face of the abyss. By YOUR quoted definition of heroism, Lovecraft absolutely is a contender here, but you’ve left him out, and you can’t have it both ways. You’ve left him out for very particular reasons, reasons that have to do with the world in which his books are written in, but you conveniently ignore those reasons for Twilight, which is again the only book on this list that is being judged SOLELY on its performance in the real world. Every other character on this list, you describe what that character does in the narrative as it relates to being a hero. Twilight is discussed in completely different terms– in terms of what it did to the “real world”. You say the only thing that matters is that “people identify with” the character, but that apparently didn’t matter for Lovecraft.

That’s the only point I’m trying to make: the quantifiers for this list were not well-thought-out at all, and so this list is basically useless as a list, let alone a “top ten list”.

LikeLike

Well you’ve already written the guts of an essay above.

You are confusing two different things there in an attempt to force through the argument – the notion of a fictional hero that people aspired to at different times and the literal impossibility of heroism in Lovecraftian fiction.

I’ll try and bridge the gap here.

Lovecraft was a materialist and his fiction carried that viewpoint to an extreme. The characters in his stories encounter evidence of beings outside our reality that exist in relation to humanity as a boot to an ant. This is a reversal of the typical mythological idea of gods being like humans – the Olympians or Asgardians had their own loves, lusts, battles – which allowed people to identify with them. Lovecraft spurns that process of identification. The Outer Gods/Elder Gods are literally unknowable, unthinkable, completely alien. To these entities all human endeavour, good/evil/heroism/villainy, is just a blip. Randolph Carter as Lovecraft’s literary alter-ego is witness to this and ultimately becomes alien himself – the implication is clear.

To what degree the writer’s own antisemitism and racism led to these views – essentially an outpouring of disenfranchised loathing towards the society he lived in – I will leave open. His fiction has a fascination for readers because it is so unflinching in its contempt for humanity – hence ‘cosmic nihilism’ above. This is why he is one of the great writers of horror and the principle upon which his popularity rests.

But this is different again from identifiation with heroes represented the values and aspirations of society down through the years. Bella is as different in what she represents for her readers as Frankenstein was to his – the good Doctor invests his family’s wealth into his genius and beats God. Bella marries into old money and becomes a suburban supermom. Shelley’s readers were an educated elite questioning their religious values. Meyer’s readers are comfortably middle-class and enjoying a romantic fantasy involving vampires and werewolves. But these books each give a snapshot of their time and what values the readership have.

LikeLike

I’m glad I wasn’t forced to call a ref in for that one. 🙂

LikeLike

…Yeah, phew, where’s Wayne when you need him…heh-heh…

LikeLike

That was enjoyable…

LikeLike

Love the condescending tone, but let me go ahead and point a few things out here:

“The Outer Gods/Elder Gods are literally unknowable, unthinkable, completely alien. To these entities all human endeavour, good/evil/heroism/villainy, is just a blip.” — Great… again, this list wasn’t ‘Top Ten Heroes of Horror As Defined By Literally Unknowable Elder Gods’. This was heroes of horror as defined by human beings. Human endeavors matter to humans. Therefore the humans in Lovecraft’s fiction matter to humans. For you to say that heroism cannot exist in this universe is, in my opinion, to see heroism in a ridiculously narrow definition.

“His fiction has a fascination for readers because it is so unflinching in its contempt for humanity – hence ‘cosmic nihilism’ above.”– That is ONE reason readers are fascinated by Lovecraft. For you to imply that you understand the concept of fascination of all Lovecraft’s readers is arrogant.

“Meyer’s readers are comfortably middle-class and enjoying a romantic fantasy involving vampires and werewolves.” — So, you’re implying that ‘enjoying a romantic fantasy involving vampires and werewolves’ is both heroic and more important than the experiences of every other left-out horror character on this list? A romantic fantasy, simply because it made money, is more heroic than Father Karras facing the darkness of his lack of faith in The Exorcist; more heroic than LeGrasse’s insistent intent on investigating the Cthulhu cult despite everything telling him to turn back?

THAT is the meat of my problem, sir. I have literally never, in any literary forum or circle, heard heroism defined so commercially or soullessly. So I’ll end this conversation here. Multiple times you indicated you created this list to “start a discussion”, and you have done that, but have simultaneously done your best to tell me I’m wrong in my viewpoint, so I don’t believe you do want a discussion and quite frankly have nothing left to say. Your list was poorly thought out, and nothing you’ve said since has convinced me otherwise.

LikeLike

No offense, but if you don’t like the list, make your own and move on. It’s an opinion piece, not a definitive list of the be all and end all. Jeebus, who has the time!!

LikeLike

I am sorry this conversation has gone the way it has. I did not mean to be condescending – the undertone of what is above is more my alarm at a disagreement becoming increasingly personal.

LikeLike

I visited multiple web pages however the audio quality for audio songs current at this website

is truly excellent.

LikeLike